Turn Your Face Towards Gaza: "Christ in the Rubble"

Why as a Christian I refuse to stand with Israel and why we must confront injustice when we see it

Hello friends,

With a heavy heart, I am returning to write about something that is of utmost importance to me, my family, and what should be to all of humanity as well. By now I am sure most of you, if not all, are familiar with the war in Gaza and the genocide Israel commits as I type.

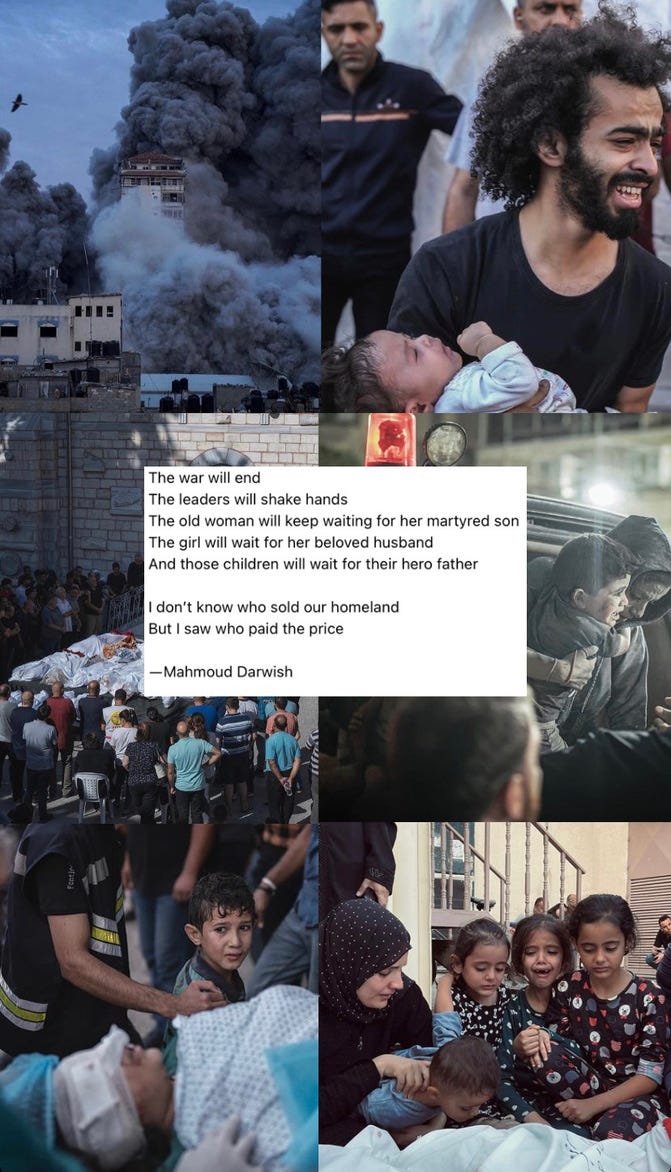

In the past 90 days, I have witnessed countless gory images and videos showing up on my Instagram. I open the app and the first post is typically an image or reel that I must press “see anyway” because it is blurred due to its horrific nature. As difficult and heart-wrenching as witnessing these things is, I refuse to turn a blind eye.

I feel that as both a human being and a Christian it is my responsibility to listen to the cries of the parents holding onto the remains of their babies and to the orphans screaming out for their loved ones under the rubble. With the amount of information coming at us in our modern age, becoming desensitized to it all or simply not looking becomes easy. Sometimes it can feel that there is too much to care about.

Nevertheless, we must look at the suffering of another human as our own problem. This inevitably will look different for everyone, but staying informed is a central goal. We have to turn our face to the issues of humanity. As liberation theologian Kelly Nikondeha writes in her book The First Advent in Palestine, “What I fail to see, I fail to lament” (21). If we distance ourselves from the pains and hurts of others, we also fail the opportunity to lament what grieves God’s heart.

She also writes, “We are called to see them, to weep with those who weep. It is, after all, a predicate to rejoicing with those who rejoice” (22). Lament is an essential part of the Christian walk and without it, my faith journey would look a lot more discouraging. It is with lament rather than constant joy that we enter into the suffering of Christ as well as the suffering of people in the world. Our responsibility is to weep with those who weep. Simply put, we should as humans have empathy and sit in the hurt of those experiencing suffering. Our lament should also prompt action. Our weepings should be followed by work towards justice and peace.

There are a few things I want to address in this piece including the following: the need for social justice, individualism versus community-centered faith, the harms of Zionism, and where God is amid genocide in Gaza. I will do my best to connect everything together, and I hope you will extend me the hospitality of reading what I have to say. I say the following from a spirit of lament and a longing for justice and true peace for the Palestinian people.

Throughout the past 90 days, I have seen a wide variety of pro-Israel posts on social media. I want to talk about a more recent tweet made by Allie Beth Stuckey, an American conservative commentator and author, that I feel encapsulates a lot of what the majority of far-right Christians falsely perceive about social justice and specifically about the Palestinian cause:

All efforts to make Christmas about what it’s not - immigration, refugees, Palestine, occupation - are attempts to avoid reckoning with the actual, uncomfortable truth of Christmas: that you need to be saved, and you’re powerless to save yourself. Within that message we face the ugliness of our sin, the reality of our fate apart from Christ, and the call to deny ourselves and follow Him. This, not social justice, is the hope of Christmas. Trade in your activism for worship, and you’ll finally get that joy you’ve been trying but failing to find.

Ironically, the Christmas story is rooted in these very subjects. Jesus himself was a refugee, born in Palestine, and under Roman occupation. We are not seeing something that is not already there in the narrative when we acknowledge this, and these poignant facts are essential as Palestinians in Gaza today face genocide. Christ’s incarnation story contains the very hope of confronting injustice and advocating for the marginalized in Palestine and globally.

Like Nikondeha goes on in her book to say: “How God entered the world matters.” Here we have a baby boy born into an occupied area in a dirty stable. What a stark, scandalous image. The King of Kings yet he chose to be born of a woman, wrapped in frail humanity, and to lie amongst the animals of a stable. This is how our God chose to enter the world.

The background of Advent itself is a particularly difficult landscape. The Israelites find themselves under the Roman empire, looking for a Messiah to come and save them from their oppressors. Amid the hopelessness, there is a young mother in a stable who has just given birth as God inherently subverts the expectations of this Messiah.

When we engage the darkness before God’s arrival, we come closer not only to the first advent but also to each one since. In Advent, we learn that God is always coming to our troubled times. (23)

Part of the hope of Christ’s incarnation is the mere fact that God cares for human suffering and affliction both on an individual level and a systemic level. He entered into our messiness, showing a better way. A way that invites us to love our enemies and our neighbors alike. A way that reconciles us to God and should reconcile us to each other.

That is what I also find saddening about tweet: this perspective lacks the fundamental work of seeking justice and mercy for all that Christianity has to offer. Situating personal salvation as the end means of Christianity does a fundamental disservice to the work of the cross. Let me unpack what I mean. Certainly, we need Christ’s sacrifice on the cross on an individual level, I do not deny that.

However, we lack the hope of our faith when we leave out the societal implications of Christ’s incarnation and crucifixion. This particular view of Christianity (one that only highlights original sin, personal salvation, and going to heaven as the end means) largely reflects the individualization of the Western church. Another way of looking at this perspective is to view one’s faith only on a vertical plane, where you are the bottom point of the vertical line and God is the top point. But Christianity was not meant to be only a vertical faith. It should be both vertical and horizontal. Vertical as being in a relationship with God on a personal level and horizontal as loving your neighbors well.

This then begs the question one professor asked in a class I took about poverty and justice: who is my neighbor? If the majority of your neighbors are people who look like you, speak like you, and live like you, what real challenge is there in loving them and looking out for them? To me, that is a comfortable faith. Yet, where do we see Jesus in the gospels? Certainly, he interacts with the powerful and healthy, those in the inner circles, but he does not stop there. He goes further to seek out his neighbors: the marginalized and vulnerable of society–lepers, the blind, prostitutes, children, and women.

I often see a lot of negative commentary from evangelical Christians about other Christians’ focus on social justice. Many view it as solely a liberal or “woke” pursuit that dismisses the Bible, as seen in Stuckey’s tweet for instance.

But I do not view my desire for justice as lacking an understanding of the significance of personal salvation. God weaves the theme of justice throughout the entirety of Scripture. His desires for justice and seeking out the vulnerable, marginalized, and oppressed are the very hope of the Gospel. Christ did not come to save only the religiously or politically powerful. He became incarnate for all. The Pharisee and the shepherd. Those in the inner circles of societies and those pushed to the margins.

Surely, it is comfortable to view the Gospel message in this individualized way. It does not make us confront the injustices around us. It does not make us care for the oppressed. We are instead able to reflect individually, focus our spiritual lives individually, and only look at sin on an individual level. The discomfort of self-reflection and sanctification then becomes the only discomfort we experience.

But let us even think of Christ’s instructions for prayer in the Lord’s prayer: “Thy kingdom come, thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven.”

This very prayer is an invitation to the work of God on earth. An invitation to seek justice, love mercy, and walk humbly with him (Mic. 6:8). If we only view Christ’s sacrifice in terms of our own selves and salvation, we miss the beauty of living out his resurrection.

I grew up hearing so much about my own sin that Jesus took on, which I do not deny is important. But how radical it would have been to hear the emphasis placed on Jesus taking on the systemic sins of the world as well with us co-laboring alongside him in that work today. What if we not only look towards Christ’s confrontation and defeat of sin on an individual basis but also on a more holistic level? Jesus not only died for a lie you told, but he also died for the systems of oppression humans have created- and that evangelicals have often contributed to. The corruption, the hunger for power, the greed of governments, etc, all of this he died for.

The problem I have with arguments like Stuckey’s is that there is an undermining tone that two things cannot be true at once. We do not need to give up the God-given hunger for justice to be a true Christian. We can be saved individually while also working towards God’s will on earth as it is in heaven.

I then wonder what she would say to Palestinian Christians like Rev. Munther Isaac, a Lutheran priest in Bethlehem, who said these words in his piece “God is Under the Rubble in Gaza”:

God is under the rubble in Gaza. He is with the frightened and the refugees. He is in the operating room. This is our consolation. He walks with us through the valley of the shadow of death. If we want to pray, my prayer is that those who are suffering will feel this healing and comforting presence.

So, when we seek justice for Palestinians, we ask ourselves the question: who is my neighbor? If, as a Christian, I cannot identify with another human being facing suffering thousands of miles from me, I am failing the job of loving my neighbor. And we see this in the American church today with the genocide in Gaza. Christians largely stand with Israel (despite the democratic nation-state of Israel today not being the same Israel of the Bible), standing with the oppressor. In doing so, they disregard their own brothers and sisters in Gaza, sheltering in the churches awaiting death by the hand of Israel.

Western Christians have greatly dismissed their brothers and sisters of faith due to a blind belief that at all costs they must support Israel. If we deny or in any way justify the violence Israel commits against Gaza, we have abandoned our own family. As Isaac goes on to write,

If there is no place for the children of Palestine and the children of Gaza in this cruel and oppressive world, then they have a place in the arms of God. Theirs is the kingdom. In the face of bombing, displacement and death, Jesus calls them: “Come to me, you who are blessed by my Father. Let the children come to me, for theirs is the kingdom.” This is our faith. This is our consolation in our pain. Amen.

Far too easy is it to sit in our comfortable homes with easy access to food, water, and electricity and make quick judgments about those we have never empathized with. When our social media feeds lack any Palestinian representation or images from those actually on the ground, justification of violence becomes quite simple. How easy it is to write articles and tweets critiquing social justice from a house unbombed, hospitals standing, and a glass of water on our coffee table.

This hyper-fixation of individualism often found in Western evangelical Christianity is damaging for both the Western church and damaging for the international church community. The denial of the significance of social justice allows room for stagnancy, especially in times like this current genocide.

Marwan Aboul-Zelof, the pastor of City Bible Church in Lebanon, wrote an incredibly insightful piece that deals with the question of Christianity and Zionism from the perspective of a Palestinian Christian. He writes the following:

This is a plea to see that the blind and insistent support of Israel not only affects our Gospel witness, but has greatly injured our ignored Christian Palestinian brothers and sisters – believers who have been faithful to Jesus since Jesus lived in Palestine.

Sadly, a large part of Christians’ lack of empathizing with the Palestinians is the fact that they have barely interacted with them. Yet, Palestinians are also part of our Christian history even if people have failed to see them. Nikondeha points out the grievous fact that for a lot of Christians who do not hear the Palestinian story, the stories they are left with are unforgiving to Palestinians:

If we see Palestinians at all, it’s through the lens of an unforgiving media that portrays them as the terrorists of the region. Invisible to us are the checkpoints, rountine home demolitions, restricted access to water, and economies strangled by design…We have empathized with Jewish pain and understoof the nature of their trauma. Yet we have failed to recognize the long lang histories, the shared places, where Palestinian families have been traumatized too. (20-21)

This distancing of ourselves from those who do not necessarily look or live like us has detrimental effects. When we fail to listen to others’ stories, we fail at loving our neighbors. In the situation faced by Palestinians in Gaza today, we go a step further: we fail at keeping our neighbors alive. The blind support of Israel by many Christians has only reinforced the genocide happening before our eyes.

Let us not forget the prophets of the Old Testament who followed the trying call of God to rebuke the Israelite’s behavior as a nation. Christians were never called to blindly support the nation-state of Israel. We were never called to blindly support anything.

Accountability of the Israeli government is essential, why? Because unlike what some politicians say or believe, human beings are not collateral damage. Israel has murdered over 22,000 Palestinians since October. 22,000 human beings with hopes, dreams, and lives to live. 22,000 humans with their own daily routine of going to school or work, eating with their family, doing their homework, and waking up and going to sleep.

When 22,000 human beings are killed, it is our human responsibility to care and take action. To call our representatives and demand a ceasefire. To turn on the TV and listen to what is happening on the ground. As a Christian, you cannot stand by as people in the very land your Savior was born are being massacred. There is no excuse or justification for genocide.

We have lost our humanity and God-given sense of justice if we even begin to provide a reason behind this violence. Palestinians deserve to live just like you and I, and the situation they face today is one that is lamentable and must be condemned.

So, I invite you to turn your eyes towards Gaza, towards the injustices, and towards your fellow human beings. If any of that makes you uncomfortable or perhaps this newsletter has made you uncomfortable, please sit with that discomfort and welcome it. It is within our discomfort that we can find a way to significant growth.

Most ardently,

Alayna Brianne

Resources for news and lament:

Insight on the ground in Gaza:

Aljazeera

This is a brilliant peace that all Christians should have to reckon with. Very insightful and well written. I’m glad to hear these kinds of voices and perspectives amidst the war.

Thank you for this piece 🙏🏻 I’ve missed your words. This is such an important topic to be addressed and you did it beautifully. I appreciate the resources you provided as well as the links to people on the ground in Gaza. Listening to your playlist now.